a practice guide for contemplating Dhamma

This is the one way, bhikkhus, a path for the purification of beings, for the surmounting of sorrow and lamentation, for the disappearance of pain and grief, for the attainment of the true way, for the realization of Nibbāna—namely, the four satipaṭṭhānas. (Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta, MN 10)

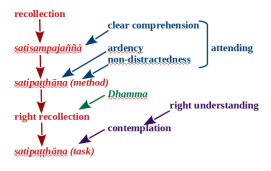

So begins the Buddha’s primary discourse on satipaṭṭhāna. Satipaṭṭhāna means literally “know-how-attentiveness.” It is the historical source of most contemplative/meditative traditions in Buddhism, including modern vipassanā or insight meditation, and the so-called “mindfulness” movement. It is also deeply implicated in samatha or tranquility meditation. The Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta is today perhaps the most studied early Buddhist text.

Satipaṭṭhāna describes the practice of contemplating Dhamma in terms of direct experience through a series of exercises, which are grouped under the four categories of body, feelings, mind and dhammas, giving us “the four satipaṭṭhānas.” Their purpose is to develop right view, whereby individual Dhammic teachings are verified in experience, familiarized and internalized, such that Dhamma becomes ultimately a matter of direct perception or responsiveness, leading to the attainment of “knowledge and vision of things as they are,” effectively enabling one to see through the eyes of the Buddha.

What you are reading is a meditators’ guide to satipaṭṭhāna practice, which is the result of my years-long very careful rethinking of what exactly the early Buddhists texts say about this critical teaching. The satipaṭṭhāna had confused me for a long time, for there seems to be astonishingly little in these early texts that is interpreted consistently or convincingly, and many details are generally ignored by modern teachers. It seemed to me that part of the confusion about what the satipaṭṭhāna texts say comes from a history of re-interpretation of key concepts. It has now been abundantly documented and is becoming widely acknowledged, for instance, that the meaning and role of samādhi or jhāna found in the commentaries, particularly in the seminal Visuddhimagga, contrast markedly with what is found in the early texts. Furthermore, much of the confusion around the satipaṭṭhāna seems to have resulted from attempting to reconcile multiple contrasting historical frameworks that don’t in principle cohere.

Prior to undertaking the current paper, I had drafted a handful of papers within the framework of the Rethinking Satipaṭṭhāna project, which I intend soon to consolidate into a book carrying that title. These papers are of an academic tone, analyzing the early texts in terms of etymology, functionality, coherence and cognitive consistency, in order to address the issues of interpretation. I have accordingly been test-driving Satipaṭṭhāna Rethought in my own meditation practice over the last couple of years, and encourage others to take if for a spin and to give me feedback. This guide leaves the academics behind in order to make the fruits of my research accessible to the Buddhist yogi. The Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta itself is a practice tutorial, taking the practitioner through a series of twenty-one targeted exercises. The present guide does the same, with additional explanations for the modern practitioner.

I should warn the student that there is necessarily a lot of Dhamma here, for the early satipaṭṭhāna was clearly intended to guide a detailed investigation of Dhamma teachings in terms of direct experience. Most modern methods treat Dhamma in a more cursory manner, but this is largely a twentieth-century artifact of streamlining satipaṭṭhāna in the more popular schools of the massive vipassanā movement in order to serve an enlarged spectrum of practitioners.

Principles of Satipaṭṭhāna Rethought

Satipaṭṭhāna Rethought is an interpretation based strictly of the earliest texts, with no reference to later derivatives, such as the Visuddhimagga or modern innovations. The following lists its most basic conclusions, and places it in the space of teachings based on the satipaṭṭhāna with which the reader may be familiar. These principles are justified in my Rethinking Satipaṭṭhāna writings.

(1) Satipaṭṭhāna contemplation is an open-ended extension of Dhammic “investigation” that begins with study.

“Right view” begins with a conceptual exposure to the Dhamma, acquired and remembered through hearing or (in later centuries) reading the Dhamma. This is followed by stages of reflection and contemplation, necessary to make sense of the Dhamma, and to verify it in practice. “Book learning” must necessarily precede or overlap contemplation. This makes the applicability of satipaṭṭhāna practice in internalizing Dhamma is open-ended.

(2) The Dhamma is in principle almost entirely subject to verification in terms of direct experience.

The Buddha invited us to “come and see,” and declared that the Dhamma is “experienced by the wise.” Although the Dhamma in many later schools became an abstract philosophical system, in the early texts it has for the most part a nuts-and-bolts basis in the direct “observables” of experience. The challenge of understanding these often sophisticated and obscure early teachings is not due to a deficit in in intellect, but, on the contrary, due to the difficulty of seeing through the abstractions we already presumptively and routinely impose on our understandings.

(3) Satipaṭṭhāna contemplation is a process whereby the practitioner develops skill in Dhamma by investigating, verifying and internalizing Dhamma in terms of direct experience.

Investigation here is a process of holding dhammas (Dhamma teachings) and observables side by side for verification. (However, as we will see, the dhamma of “non-self,” prominent in the sutta, is an anomalous case, which requires an modification of this technique, such that observables are expected repeatedly to fail to verify the presumed “self.”) Repeated investigation and verification internalizes dhammas so that they are woven into the fabric of experience, so that in the end Dhamma becomes how we perceive intuitively and act spontaneously in our experiential world. This process is typical of “skill acquisition” in a vast variety of areas, whereby our “know how,” at first explicit and effortful, becomes internalized as implicit and effortless. ( More about this below.)

(4) Samādhi or jhāna is integral and critical to the fulfillment of satipaṭṭhāna contemplation.

Samādhi locks in our engagement in the task of investigation, the higher jhānas (second through fourth) filter out spurious abstract conceptualizations and narratives, and samādhi is necessary to encourage insight and the internalization of intuitive understanding.

(5) The ultimate function of satipaṭṭhāna contemplation is the attainment of knowledge and vision of things as they are.

“Knowledge and vision” is the precursor of awakening.ii Through the practice of satipaṭṭhāna that we learn to see through the eyes of the Buddha. This, in conjunction with the practice of virtue, brings us close to Nibbāna.

MORE …

Useful Links:

Useful Links: Samādhi is an anomaly for most of us in the way a human mind is supposed to work, and yet there it is. Accounting for it has caused endless confusion among modern scholars and teachers, many simply attributing mysterious or mystical powers to it, others viewing it as superfluous in Buddhist practice. Yet the weight given to this quite state in the early texts cannot be overlooked. It holds the prominent place as the ultimate factor of the noble eightfold path, it is declared to consolidate all previous factors on the path and to be indispensable in the early texts for the highest attainments: knowledge and vision, and liberation.

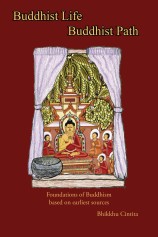

Samādhi is an anomaly for most of us in the way a human mind is supposed to work, and yet there it is. Accounting for it has caused endless confusion among modern scholars and teachers, many simply attributing mysterious or mystical powers to it, others viewing it as superfluous in Buddhist practice. Yet the weight given to this quite state in the early texts cannot be overlooked. It holds the prominent place as the ultimate factor of the noble eightfold path, it is declared to consolidate all previous factors on the path and to be indispensable in the early texts for the highest attainments: knowledge and vision, and liberation. A 12-week course on the fundamental concepts of Buddhism based on the earliest sources. We will use Bhikkhu Cintita’s book Buddhist Life/Buddhist Path as a text, which is available as download or hard copy. Copies are also available at the Sitagu Buddhist Vihara in Austin and the Sitagu Dhamma Vihara in Minnesota. Please join us. You’ll learn a lot about early Buddhism. Join us, you’ll learn a lot about Buddhism.

A 12-week course on the fundamental concepts of Buddhism based on the earliest sources. We will use Bhikkhu Cintita’s book Buddhist Life/Buddhist Path as a text, which is available as download or hard copy. Copies are also available at the Sitagu Buddhist Vihara in Austin and the Sitagu Dhamma Vihara in Minnesota. Please join us. You’ll learn a lot about early Buddhism. Join us, you’ll learn a lot about Buddhism.